Over the years, many countries have defaulted, causing significant and complex far-reaching consequences for domestic and global economies. Default is when a country fails to meet its financial obligations and is unable or unwilling to repay creditors [1]. Understanding the causes and economic, social, and political impacts is crucial to mitigate the devastating effects on the economic world.

A country can default for various reasons, from high debt burden to political instability or economic stagnation [1]. High debt levels are the most common economic factor that can cause a country to default. When a country borrows excessively, the strain on its finances increases, making it difficult to repay loans and interests. If the country’s economic output (GDP) is low, it can lead to a debt overhang (a debt burden so large that an entity cannot take on additional debt to finance future projects)[2].

Argentine Great Depression:

The 1998-2002 Argentine Great Depression was a severe economic crisis that engulfed Argentina. High levels of debt, devalued currency, and a fragile banking system ultimately led Argentina to default on its debt in 2001.

The Convertibility Plan, which pegged the Argentine peso to the U.S. dollar, initially brought stabilisation, ending hyperinflation [3], allowing the economy to grow at an average rate of 6% annually through 1997. The first set of recessions was short-lived; however, the second recession – which started in the second half of 1998 – created economic stagnation and a persistent current account deficit [4].

The fixed exchange made Argentine exports more expensive compared to countries with flexible exchange rates causing Argentina to import more than it exported. The fixed-rate prohibited the government from devaluing the currency to boost exports or stimulate the economy. Argentina accumulated a significant amount of external debt because it relied on foreign loans to cover the deficit from the overvalued peso. In December 2001, Argentina defaulted on its $132 billion sovereign debt, the largest default in history at the time.

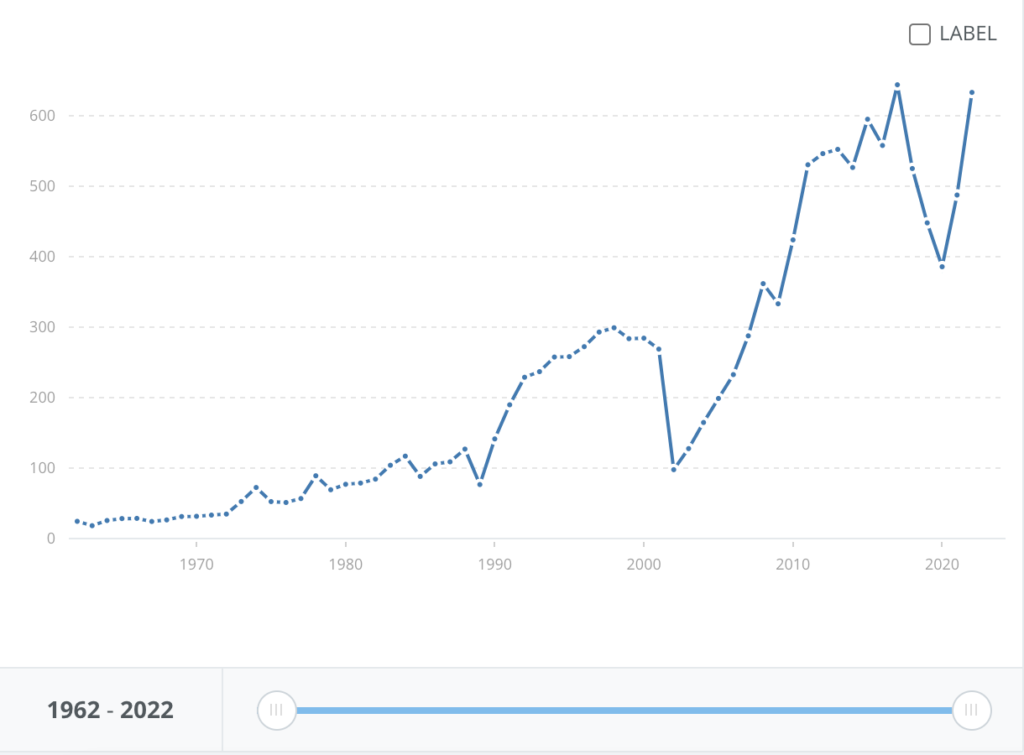

^GDP (current US$) – Argentina [Graph from The World Bank Data]

Argentina plunged into economic recession after the default. Argentina abandoned the fixed exchange rate, which allowed the Argentine peso to float freely. This resulted in a sharp currency depreciation, inflation, and decreased the population’s purchasing power. GDP plummeted, unemployment skyrocketed, and poverty levels surged. The proportion of Argentines below the officially defined poverty line jumped from 38.3 per cent in October 2001 to 57.5 per cent a year later[3].

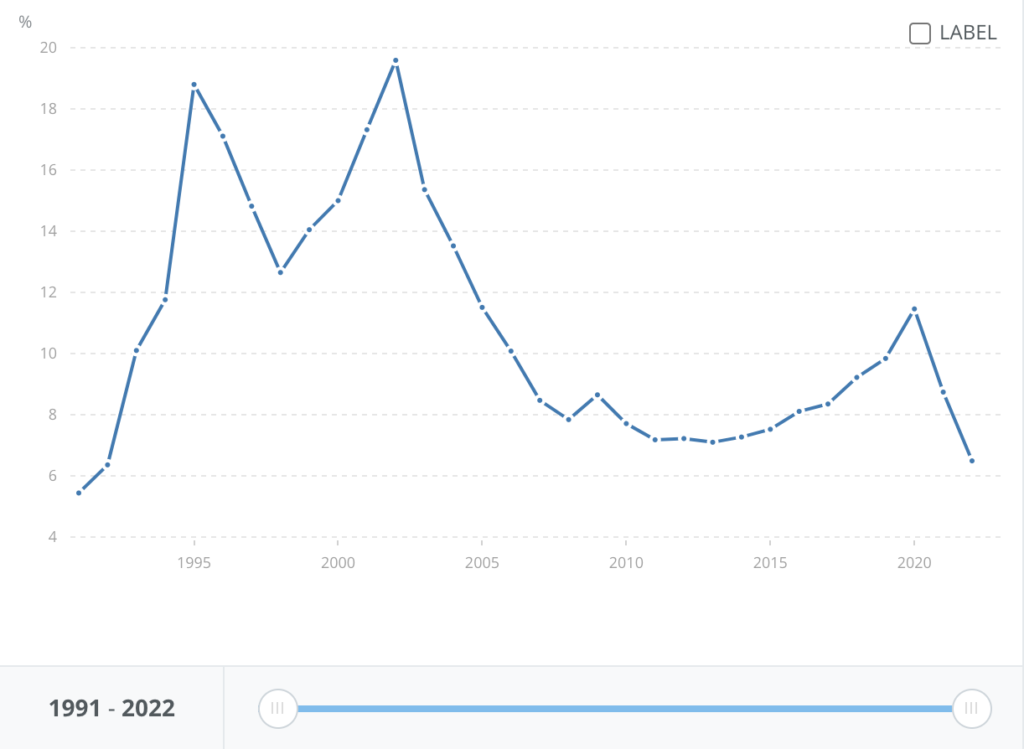

^ Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modelled ILO estimate) – Argentina [Graph from The World Bank Data]

After years and a lengthy process of negotiation and reforms, Argentina gradually recovered from the crisis.

Russian Ruble Crisis

The Russian default occurred in 1998 and was a financial crisis triggered when the Ruble lost over two-thirds of its value in three weeks[5]. Following the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia had to deal with several problems, including the inability to put economic reforms into practice, poor economic management, falling oil prices, and other external shocks that would affect neighbouring countries.

Russia imported many goods from the former Soviet Union because it was supposed to help those nations. Loans from foreign sources financed Russian investments. The Ruble eventually lost value when it could not repay those foreign loans.

This led to corruption and capital flight becoming prevalent – wealthy individuals and businesses moved their assets out of the country, making it difficult for the government to manage its financial system. Overspending and a lack of financial restraint contributed to Russia’s unmanageable debt load, which eventually caused international investors to lose faith in Russia’s ability to repay its debt.

In the late 1990s, there was a sharp decline in oil prices, and because Russia heavily relied on oil exports for its revenue, the government suffered from a budget deficit. Due to the country’s heavy reliance on oil exports, it was vulnerable whenever there were significant changes in oil prices, showing that Russia’s economy needed to be more diversified.

In early August 1998, the Russian stock, bond and currency markets were under severe pressure. Defending the ruble depleted Russia’s foreign reserves [6]. Once depleted on August 17, 1998, the Russian government defaulted on approximately $40 billion of its debt. The default led to a severe financial and economic crisis in Russia, with inflation skyrocketing and businesses and banks facing insolvency. The crisis had a ripple effect on global financial markets due to a 90-day suspension on payments by commercial banks to foreign creditors[5].

As part of its efforts to control the situation, the Russian government devalued the ruble and requested aid from the IMF. While these actions helped restore some stability, it took multiple years before Russia could fully recover.

Russia experienced a technical default in 2022 because of its inability to fulfil its obligations in foreign currencies that were in U.S. dollars. Following the invasion of Ukraine, the United States and its allies imposed sanctions on the Russian government, punishing the country’s largest financial institutions like Gazprom and the central bank. [7].

< [16] In just two weeks, the Russian rouble’s value against the U.S. dollar dropped by more than 40%.

The Biden administration had initially permitted Russia to continue repurposing substantial funds held in U.S. financial institutions to make required payments on its sovereign debt. However, after considering the current situation in Ukraine, the Treasury Department has prohibited Russia from withdrawing funds held in U.S. banks to pay off its debt obligations. [8].

The Russian government argued that Western sanctions effectively created the default since the country had plenty of foreign currency in its now-frozen accounts. [9] The Russian government further contended that the sanctions severely restricted their access to these frozen accounts, exacerbating the default situation. They emphasised that without such sanctions, they would have been able to utilise their foreign currency reserves to meet their financial obligations and avoid default.

Pakistan’s Balance of payment crisis

The 1998 balance of payments crisis in Pakistan referred to a severe economic situation caused by a significant imbalance between the country’s foreign currency inflows and outflows.

Until 1998, Pakistan had an excellent record of meeting its external debt obligations. However, during the 1998 foreign exchange crisis, foreign exchange reserves fell to less than $450 million in November and loan repayments totalled more than $1.5 billion [10].

Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves began to deplete rapidly, and Pakistan faced difficulties in servicing its external debt obligations due to the balance of payments crisis. The country defaulted on its external debt payments in May 1998, resulting in a loss of investor confidence and a drastic depreciation of the Pakistani rupee.

Pakistan sought assistance from the International Monetary Fund in response to the crisis (IMF). The IMF provided financial assistance and aid packages to stabilise the economy, restore investor confidence, and resolve the underlying structural issues that contributed to the crisis.

However, this wasn’t Pakistan’s first debt crisis. Pakistan’s debt crisis in 1958 resulted from several economic and political factors. In 1958, Pakistan experienced a military coup led by commander-in-chief Muhammad Ayub Khan, establishing a military government [11]. Before the coup, Pakistan was already facing economic difficulties, including a high fiscal deficit and a balance of payments problem.

The political instability and transition of power brought on significant impacts on the country’s economy. The country’s imports surpassed its exports, resulting in a large current account deficit and a drain on foreign exchange reserves. In an attempt to balance of payments crisis, the Pakistani rupee was devalued in relation to other currencies. This devaluation was intended to boost exports and reduce the trade deficit but ended up increasing the burden of foreign debt.

Pakistan requested help from the International Monetary Fund in response to the debt crisis (IMF). The IMF provided financial assistance while placing limits on economic reforms. The tax increases proposed in the 1958-59 budget were expected to raise Rs 240 million in revenue, which equated to about 5% of the money supply at the end of 1957 [12]. The Pakistani government also implemented economic sanctions, such as cutting public spending and raising taxes.

Venezuela:

Venezuela has defaulted on its debt 11 times in its history. The country that first defaulted in Venezuela has defaulted on its debt 11 times in its history. The country first defaulted in 1826, just a few years after gaining independence from Spain. Since then, Venezuela has gone through several debt crises and defaults, with the most recent occurring in 2017. Venezuela’s ongoing economic and political crisis led to the country’s default in 2017.

Because it depends heavily on oil revenue, Venezuela experienced a severe economic downturn in 2014 due to a sharp decline in world oil prices. President Nicolás Maduro’s administration struggled to control the crisis, leading to hyperinflation, essential item shortages, and a rapidly deteriorating economy.

The government’s excessive money printing caused a hyper inflationary spiral to cover budget deficits, a decline in economic output and a lack of confidence in the Venezuelan bolivar, the country’s official currency. The local currency’s purchasing power is reduced by hyperinflation, making it harder for people to afford necessities like food and shelter. Prices skyrocketed, and the bolivar’s value fell sharply. This resulted in extreme poverty levels as the cost of goods increased daily. Millions of Venezuelans migrated out of the country hoping to better access to necessities, putting pressure on the neighbouring countries.

As the crisis worsened, Venezuela struggled to pay its obligations under its external debt. Venezuela missed several debt payments in November 2017, which prompted credit rating agencies to declare the nation in default. The government had billions of dollars’ worth of outstanding bonds, and the default resulted in many legal disputes with bondholders and creditors.

Venezuela’s already dire economic circumstances were made worse by the default. It further restricted the country’s access to international financing as investors grew cautious of lending money to the Venezuelan government. As a result, the economic crisis and the humanitarian situation worsened, with severe shortages of food, medicine, and other essential goods.

Venezuela’s default in 2017 was a pivotal event in the country’s economic collapse, further isolating it from the international financial community. The consequences of Venezuela’s default continue to impact the country’s economy.

Lebanon:

Lebanon defaulted on its sovereign debt in March 2020 for the first time due to a severe economic crisis. For years, Lebanon’s debt load has been steadily rising, and by 2020, it had reached unsustainable levels, with one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the world. The post-war economic development model of the nation, which benefited from significant capital inflows and international support in return for promises of reforms, is bankrupt [13]

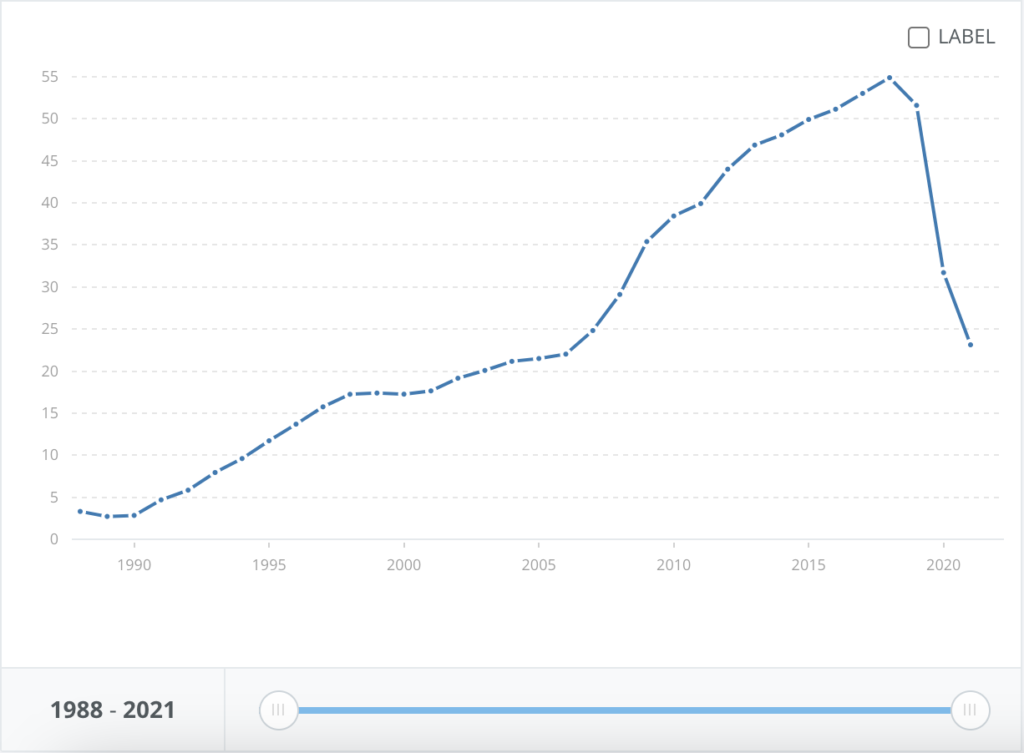

According to estimates from the World Bank, Lebanon’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) decreased by 58% between 2019 and 2021. [14]

^GDP (current US$) – Lebanon [Graph from The World Bank Data]

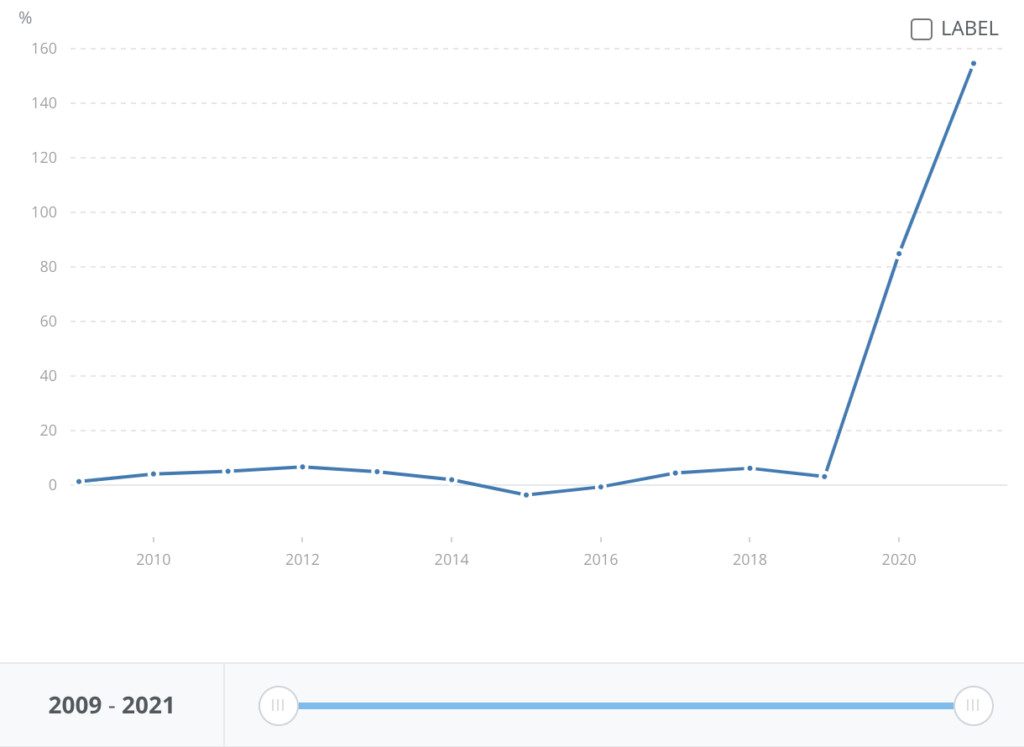

The government’s inability to repay a $1.2 billion Eurobond in March 2020 triggered the default causing the economy and people of Lebanon to suffer greatly. There has been a significant decline in purchasing power, a sharp devaluation of the Lebanese pound, and extremely high inflation. The nation has also experienced food, medicine, and fuel shortages.

^ Inflation, consumer prices (annual %) – Lebanon [Graph from The World Bank Data]

The nation is negotiating a bailout package with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to stabilise the economy and implement crucial reforms. These negotiations have been difficult, though, because they call for strong political will and dedication and address the root causes of the crisis, such as mismanagement and corruption.

Even though the country’s government reached a preliminary agreement with the IMF on the economic governance reforms required to secure new IMF funding, the Lebanese economy continued to struggle in 2022. Another requirement is that Lebanon negotiates a debt restructuring with private foreign creditors. Two years after the default, talks on such a deal had yielded no apparent progress as of mid-2022 [9]. In 2023, Lebanon currently remains in a state of economic turmoil.

Consequences of default:

Defaulting on financial obligations can have severe consequences for a country.

Lose access to international markets: investors and lenders become wary of extending credit to those countries that have defaulted, leading to higher borrowing costs or even a complete cut-off from capital markets. This restricts the country’s ability to borrow and finance its operations, resulting in reduced economic growth prospects. It can take years, if not decades, to rebuild trust and regain access to international financial markets.

Economic Recession and Financial Instability: Default can trigger or exacerbate an economic recession. It can lead to a decline in investor confidence, capital flight, and a contraction in economic activity. The lack of access to financing can hinder government spending on crucial sectors such as infrastructure, healthcare, and education, further exacerbating the economic downturn. Financial instability and volatility may also arise, leading to currency devaluation, inflation, and banking system risks.

Downgrading of Credit Ratings and investor confidence: Default is an obvious indicator of financial trouble, which rating agencies use to determine a country’s creditworthiness [15]. When a country defaults, it creates a loss of confidence in its ability to repay its debts, making it even more challenging to attract foreign investment and access affordable financing.

Legal Consequences and Litigation: Default can lead to legal consequences, including lawsuits from creditors seeking to recover their investments. Creditors may take legal action to seize assets or seek repayment through international arbitration or court systems. These legal battles can be costly and time-consuming, further straining the country’s financial resources.

Social and Humanitarian Consequences: Default can have significant social and humanitarian consequences. The burden of the crisis is often borne by the most vulnerable populations, exacerbating poverty and inequality.

Preventative measures and solutions:

A country can take different preventative measures to manage and overcome a debt crisis that can lead to a default.

Fiscal management: Governments should focus on maintaining a balanced budget, reducing budget deficits, and ensuring sustainable levels of public debt. This includes improving revenue collection, rationalising public spending, and implementing effective debt management strategies.

Economic Diversification: Over dependence on a single sector or source of revenue can make a country vulnerable to external shocks and fluctuations. Diversifying the economy and reducing reliance on volatile sectors can help mitigate risks and enhance resilience. They can do this by promoting sectors with long-term growth potential, such as technology, renewable energy, or manufacturing.

Implementing governance and structural reforms: Enhancing transparency, accountability, and anti-corruption measures can help prevent mismanagement of public funds and ensure efficient allocation of resources. Strengthening legal frameworks, promoting independent judiciary, and enforcing contracts can also improve investor confidence and facilitate economic growth. Structural reforms include improving business environments, promoting competition, streamlining regulations, and addressing labour market rigidities. Structural reforms can enhance productivity, attract investment, and drive sustainable economic growth.

Promoting Sustainable Development: Focusing on long-term sustainable development can help prevent future debt crises. Investing in human capital, education, healthcare, and infrastructure can create a strong foundation for economic growth and reduce the likelihood of default. Promoting inclusive growth and addressing social inequalities can contribute to long-term stability and resilience.

Countries must prioritise fiscal management, good governance, and sustainable economic policies to mitigate the risk of default and facilitate a path towards financial recovery after defaulting.It is important to note that each country’s situation is unique, and the specific measures required to prevent default may vary. Similarly, the consequences and severity of default can vary depending on the country’s economic and political circumstances.

Often, factors can interact and can create a vicious cycle, making it increasingly difficult for a country to avoid default.

Reference:

- (n.d.). Why and When Do Countries Default? [online] Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/102413/why-and-when-do-countries-default.asp#:~:text=But%20it%20does%20happen. [Accessed 15 Jul. 2023].

- Kagan, J. (n.d.). Debt Overhang. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/debtoverhang.asp [Accessed 15 Jul. 2023].

- Saxton, J. (2003). ARGENTINA’S ECONOMIC CRISIS: CAUSES AND CURES. [online] Available at: https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/5fbf2f91-6cdf-4e70-8ff2-620ba901fc4c/argentina-s-economic-crisis—06-13-03.pdf [Accessed 16 Jul. 2023].

- org. (2019). The Role of the IMF in Argentina, 1991-2002, Issues Paper/Terms of Reference for an Evaluation by the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO), July 2003. [online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/External/NP/ieo/2003/arg/index.htm [Accessed 18 Jul. 2023].

- Coyle, C. (2022). Russia’s 1998 currency crisis: what lessons for today? [online] Economics Observatory. Available at: https://www.economicsobservatory.com/russias-1998-currency-crisis-what-lessons-for-today [Accessed 17 Jul. 2023].

- Chiodo, A.J. and Owyang, M.T. (2002). A Case Study of a Currency Crisis: The Russian Default of 1998. Review, [online] 84(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.20955/r.84.7-18.

- The Balance. (n.d.). What Caused the Russian Ruble Crisis? [online] Available at: https://www.thebalancemoney.com/what-caused-the-russian-ruble-crisis-1978828 [Accessed 16 Jul. 2023].

- Stein, J. and Gregg, A. (2022). U.S. impedes Russia’s debt payments as new sanctions package emerges. Washington Post. [online] 5 Apr. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2022/04/05/russia-default-banks-currency/ [Accessed 15 Jul. 2023].

- Staff, I. (n.d.). Sovereign Default. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sovereign-default.asp [Accessed 18 Jul. 2023].

- 1997-2001.state.gov. (n.d.). Technical Difficulties. [online] Available at: https://1997-2001.state.gov/issues/economic/trade_reports/1999/pakistan.pdf [Accessed 16 Jul. 2023].

- (2023a). 1958 Pakistani military coup. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1958_Pakistani_military_coup [Accessed 18 Jul. 2023].

- ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/archive/pdf/ar1958.pdf [Accessed 17 Jul. 2023].

- World Bank. (n.d.). Lebanon’s Crisis: Great Denial in the Deliberate Depression. [online] Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/01/24/lebanon-s-crisis-great-denial-in-the-deliberate-depression#:~:text=In%20fact%2C%20Lebanon [Accessed 15 Jul. 2023].

- Derhally, M.A. (2023). Lebanon’s business conditions hit 10-year high as activity and demand rise. [online] The National. Available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/economy/2023/07/05/lebanons-business-conditions-hit-10-year-high-as-activity-and-demand-rise/#:~:text=Lebanon [Accessed 18 Jul. 2023].

- (n.d.). What happens when a country defaults? [online] Available at: https://cointelegraph.com/learn/what-happens-when-a-country-defaults [Accessed 18 Jul. 2023].

- barrons.com. (n.d.). The Russia Uprising Is Over. Why the Russian Ruble Is Still Dropping. [online] Available at: https://www.barrons.com/visual-stories/russia-uprising-dollar-ruble-wagner-putin-855b955e [Accessed 16 Jul. 2023].

Well portrayed.

Hi Ammarah! Your article on financial collapses somehow crossed my screen today. Usually, economics articles can get pretty boring, but yours was super engaging and detailed. Loved the conclusion about the ‘vicious cycle’. Just wanted to say great job on this!