Dyslexia is a reading disorder that disrupts how your brain processes written language due to problems identifying speech sounds and learning how they relate to letters and words. It’s imperative not to confuse dyslexia with low intelligence, hearing or vision. Research has shown no link between intelligence and dyslexia and often individuals with dyslexia go on to achieve great success in their careers. Dyslexia is rather a result of individual differences in areas of the brain responsible for language processing. Dyslexia is estimated to affect 15%-20% of people worldwide[1].

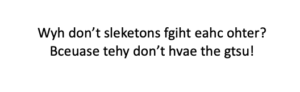

Victor Widell’s website is a great way to understand how individuals with dyslexia see words.

Don’t confuse this with typoglycemia which is a neologism used to describe the jumbled letters in a word caused by rearranging the middle letters– the first and last letters stay in their position.

Dyslexia Across the Lifespan: From Childhood to Adulthood

Before you learn to read, you learn to speak. The first step in speaking is learning simple sounds. As you get older, you learn to connect these sounds to form words, and then sentences[2]. Dyslexia comes into play when one cannot associate sounds with certain letters or words. It tampers with your brain’s ability to “decode” written material through spoken language. When you read, your brain has a hard time comprehending what you read, especially when it comes to dissecting words into sounds or connecting letters to sounds.

Regardless of gender, dyslexia can be diagnosed at any point of life and is usually a lifetime condition. These are some symptoms to look out for[3]:

In Children:

- Late talking

- Slow to learn new words

- confusing similar sounds

- Problems with rhyming or nursery games

- Reading below age level

- Trouble remembering sequences

- Takes extra time on reading/writing tasks

In Teens and Adults:

- Difficulty reading, especially aloud

- Trouble finding the right words

- Poor spelling

- Difficulty storing or retrieving words

- Trouble summarizing stories or learning languages

- Difficulty with math word problems

- Trouble learning a foreign language

It’s important to remember having one of the above symptoms doesn’t mean a person has dyslexia. Consulting a professional and getting tested is the appropriate way to diagnose dyslexia.

Types of Dyslexia

Developmental:

Developmental dyslexia is present from birth. This includes primary and secondary dyslexia:

- Primary: caused by an inherited genes or a genetic mutation. This affects 40&-60% of children whose parents have it and is more frequent in men than women[4]. Primary dyslexia is characterised by malfunction in the left hemisphere of the brain, which is engaged in reading and has an impact on language processing.

- Secondary: Caused by foetal neurological development abnormalities.

Acquired:

Acquired dyslexia (AKA trauma dyslexia/alexia) develops during childhood or adulthood as a result of an injury or disease such as stroke, dementia or brain damage. This type of dyslexia causes a loss of reading skills, unlike the other types that make it difficult for youngsters to learn to read and spell. Fortunately, people can “relearn” to read to some extent.

Subtypes of dyslexia:

Phonological:

A person who has trouble with phonetics is said to have phonological dyslexia, also known as dysphonetic or auditory dyslexia. This is a problem with “coding,” or connecting words and letters to their corresponding sounds and, hence, to their meaning in language. It can be tough to break down words into syllables and sounds and then combine those sounds to produce a word.

Deep:

Deep dyslexia is a type of acquired dyslexia caused by trauma or damage to the left hemisphere. When someone has severe dyslexia, they either make semantic errors or “misread” the word, believing it to be something different. This should not be confused with common grammar errors like ‘to, two, and too’ and ‘their, they’re and there’. [5]

Deep dyslexia can also appear when a person cannot recollect previously learnt words and substitutes what they “think” the term should be. Ironically, some widespread preconceptions about individuals with dyslexia, such as the belief that they perceive things backwards, are founded on the mistakes that people with deep dyslexia make.

Surface:

Surface dyslexia is defined as the inability to read words that are spelled differently than how they are spoken. Sight words frequently contain silent letters or variances from standard spelling standards, making them difficult to learn in the first place. E.g. Wednesday and island.

These people may struggle to learn and remember words because they have difficulty recognising them. To learn sight words, the ordinary person just memorises their spelling. This is also a frequent method of reading in foreign language training. They will teach grammar, but vocabulary is frequently established with sight words. Surface dyslexia is uncommon in general and is frequently associated with acquired dyslexia. However, it does develop in children on occasion.

Rapid Naming Dyslexia:

Individuals with rapid naming dyslexia have difficulty processing letters and numbers quickly, which leads to lowered reading times. They are sometimes slow to answer orally, regularly replace words or leave phrases out entirely, make up gibberish words in place of real language, and may use gestures instead of speech.

Double Deficit Dyslexia:

It is not rare to have multiple types of dyslexia.

Rapid naming deficit dyslexia and phonological dyslexia are the two forms that co-occur most often. Double deficit dyslexia is the term used to describe someone who possesses both of these. A person with double deficit dyslexia exhibits deficiencies in both naming speed and phonological processing[6]. So, this individual struggles with naming speed and word sound identification. This kind of dyslexia, which combines phonological and quick naming, is not rare but is generally recognised as the most severe kind.

Visual Dyslexia:

Visual dyslexia is most likely caused by abnormalities with the areas of the brain that handle visual processing. People with visual dyslexia frequently have trouble recalling what they have just read[7]. This type interferes with visual processing, causing the brain to receive an incomplete image of what the eyes view. Visual dyslexia impairs the capacity to learn how to spell or form letters since both need the brain to retain the correct letter sequence or shape, which disrupts the learning process.

Often when people with dyslexia are reading, they often switch, rotate and mirror letters in their minds. For them, letters ‘jump around’. This is made worse by typical typefaces as they base some letter designs on others, creating ‘twin letters’ for people with dyslexia. A Dutch designer in 2014, Christian Boer created a dyslexic friendly font to aid individuals with dyslexia to read better. Each character has key characteristics differentiating letters that may seem similar in appearance. These key characteristics may include an exaggerated stick and tail length or heavy bold lines on some areas of the letters.

Associated with dyslexia:

Not all learning problems associated with dyslexia are actually dyslexia. For example, a person may be diagnosed with dyslexia while simultaneously having:

Dysgraphia:

A disorder that causes difficulties with writing or typing, often due to eye-hand coordination issues. It can also hinder direction- or sequence-oriented operations like knot tying or repetitive jobs.

A person with dysgraphia has handwriting that may display several irregularities, such as[8]:

- Inconsistent spacing of letters and words

- Missing or swapped letters

- Odd spellings

- Differently shaped or sized letters

- Illegibility

Dyscalculia:

3-6% of children suffer from this disease and it occurs when someone struggles with numbers. The symptoms can differ, but frequently, a person will have trouble telling time or remembering and organising numbers.

Dyspraxia:

AKA “clumsy child syndrome.” A child struggles with fine motor skills and the coordination of their body movements. E.g. writing, buttoning clothes, tying shoelaces.Furthermore, the child might have trouble controlling the muscles in his face to make sounds, which could lead to a stutter in speech.

Left right disorder:

A person experiencing left-right confusion finds it difficult to identify left from right. People who suffer from this disease could find it difficult to interpret maps or directions. Though the term is misleading, this is sometimes referred to as directed dyslexia. It is not a type of dyslexia, but it may manifest as dyslexia, similar to dyscalculia.

ADHD:

This disorder is characterised by hyperactivity, impulsive behaviour, and difficulties maintaining focus. Dyslexia and ADHD frequently coexist. Up to 35% of those with ADHD also have dyslexia, while roughly 15%-24%, of those with dyslexia also have ADHD.

Neuroscience and Dyslexia:

Dyslexia seems to have a variety of causes;

Differences/disruptions in brain development and function:

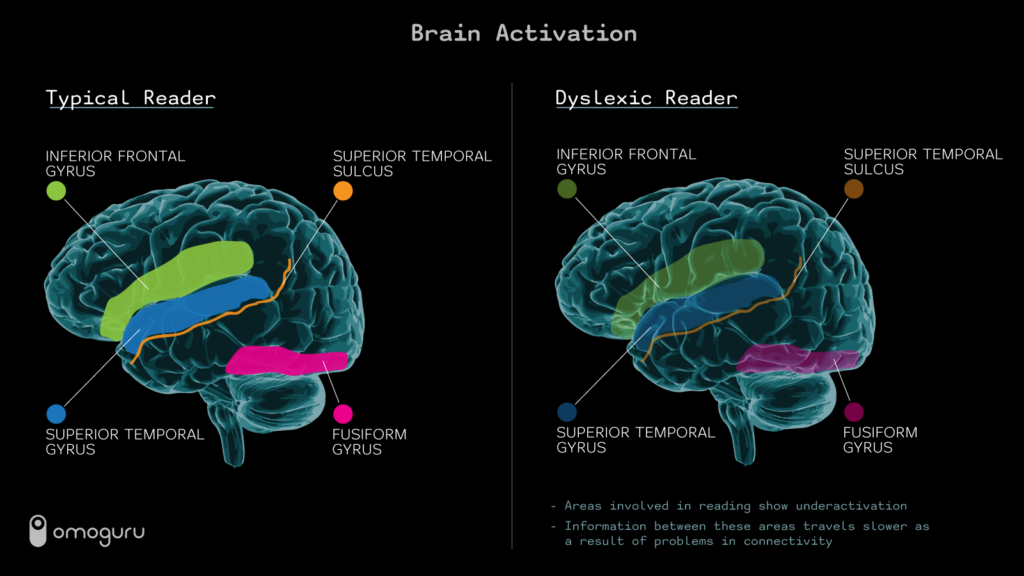

Studies reveal anatomical, functional, and chemical deviations in the brains of dyslexics.

Certain dyslexic patients exhibit reduced activity in reading-related regions of the left hemisphere of the brain like the cerebral cortex and cerebellum. Additionally, it has been shown that dyslexic people have structurally different corpus callosums which is a bundle of nerve fibres connecting the left and right hemispheres of the brain. Such changes might affect how information travels between the hemispheres, which could have an effect on reading abilities.

PET scans and other neuroimaging methods like MRIs and fMRIs have also offered evidence. The left inferior frontal gyrus, which is critical for phonological processing (the ability to identify and manipulate sounds in language), has typically decreased grey matter density in dyslexic people.

According to the cerebellar theory of dyslexia, some people experience difficulties with fluency as a result of impaired cerebellum-controlled muscular action, which affects word production through the tongue and face muscles. Some dyslexic children’s motor task and balance issues could point to a cerebellar component contributing to their reading difficulties.

Genetics:

Dyslexia is hereditary. If one of the parents has dyslexia, there is a 30% to 50% probability that the child will also have it. Researchers have looked for functional and structural abnormalities in the brain tissue of deceased individuals who were diagnosed with dyslexia. Studies have shown that certain brain regions—primarily in the left hemisphere—related to language comprehension grow irregularly.

Both the fusiform gyrus, which is in charge of visual word identification, and the angular gyrus, which links visual and aural information, are smaller than usual. They also demonstrate variations in neuronal density and connectivity between different brain regions, which impact language processing and reading abilities. Many genes have been connected to dyslexia, including DYX1C1 on chromosome 15 and DCDC2 and KIAA0319 on chromosome 6[9].

Gene-Environment:

Another explanation of dyslexia is the intersection between hereditary and environmental factors. This has been explored through twin studies that calculate the variance percentage attributed to a person’s environment vs. the percentage attributed to their genes.

Research suggests that heredity has a greater impact in supportive environments compared to less optimal ones, despite contextual factors such as parental education and instructional quality.

Given how strongly the environment influences learning and memory, epigenetic modifications are likely to have a considerable impact on reading skills. Epigenetic processes are examined using measures of gene expression, methylation, and histone modifications in the human body; however, the conclusions of these research have limitations when applied to the human brain.

Other causes include:

- Premature birth or low birth weight

- Exposure to harmful substances during pregnancy

- Infections in the mother during pregnancy

- Early childhood stress exposure.

Language[9]:

The difficulty of learning to read in a particular language is heavily influenced by its orthographic complexity—the relationship between written symbols and their corresponding sounds. Languages differ in how well their writing systems map letters to sounds, which influences how quickly people, particularly those with dyslexia, learn to read.

English and French have deep phonemic orthographies, resulting in complex spelling systems. These languages have numerous kind of rules:

- Letter-Sound Correspondence: Individual letters sound different depending on the word and their position in the word.

- Syllables and Morphemes: Decoding words must take into account full syllables and morphemes (the smallest units of meaning). This complexity makes it more difficult for individuals with dyslexia to master reading in these languages.

Languages with shallow orthographies, such as Greek, Finnish, Norwegian, have a clear relationship between letters and sounds. People with dyslexia find it easier to learn these languages since the spelling and pronunciation rules are simpler and more consistent.

There are extra difficulties when writing systems use logographic letters, like Chinese and Japanese, which are symbols representing words or morphemes. Because there are no clear letter-sound correspondences and learners must memorise a vast number of symbols, dyslexic students frequently struggle with logographic systems.

This demonstrates why dyslexia can emerge and appear differently in different languages.

Educational Strategies to Improve Cognitive Processing in Dyslexia

It is imperative that you begin addressing your child’s dyslexia as soon as you find out about it. As of right now, dyslexia is not treated by drugs[10]. Dyslexia is a spectrum disorder with varying degrees of impairments, and an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is essential for proper word decoding. Working with a qualified specialist can help children learn new reading abilities. Additional intervention strategies include audiobooks, multisensory teaching approaches, and note-taking support.

The most important of all – with a solid support system, most people with dyslexia can learn to read fluently.

Reference:

- International Dyslexia Association. “Dyslexia Basics.” org, International Dyslexia Association, 2016, dyslexiaida.org/dyslexia-basics/.

- Shaywitz, Sally. “What Is Dyslexia?” Yale Dyslexia, 2017, dyslexia.yale.edu/dyslexia/what-is-dyslexia/.

- “What Is Dyslexia?” WebMD, WebMD, 12 Apr. 2017, www.webmd.com/children/understanding-dyslexia-basics.

- “Kathleen Dunbar MFT.” net, 2024, kathleendunbar.net/different-kinds-of-dyslexia.

- “What Are the Different Degrees of Dyslexia That Exist?” Learning Center for Children Who Learn Differently, Their Teachers and Parents in Dubai, Middle East, 18 Sept. 2021, www.lexiconreadingcenter.org/degrees-of-dyslexia/.

- “Learn about the Different Types of Dyslexia & How to Identify Them.” Neurohealthah.com, 16 May 2021, neurohealthah.com/blog/types-of-dyslexia/.

- “The Types of Dyslexia.” Verywell Health, www.verywellhealth.com/types-of-dyslexia-5214423#toc-types-of-dyslexia.

- Cleveland Clinic. “Dysgraphia: What It Is, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 15 June 2022, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23294-dysgraphia.

- Wikipedia Contributors. “Dyslexia.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Nov. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dyslexia.

- —. “Dyslexia: Finding a Way to Overcome Reading Difficulties.” Cleveland Clinic, 11 Apr. 2023, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6005-dyslexia.